What comes after brand purpose?

The death of brand purpose, long-heralded, seems as though it might be on the horizon. But what comes next?

The idea of “brand purpose” has slowly engulfed the world of consumer brands for the past decade. Awards ceremonies are dominated by it; every brand now takes a stand on issues of racial justice, gender equality, period poverty, the plight of refugees, and countless other issues, many of them utterly divorced from the activities of the businesses behind the brands.

Declarations of the death of brand purpose are growing in volume and frequency in recent months, the consequence of years of opposition from both ethical business wonks and traditional, efficacy-driven, commercial marketeers.

The latest compelling account is from Nick Asbury, who writes in Purpose wins. Who loses? of the collective delusion and self-serving hypocrisy of brand purpose. Crucially, though, I think Asbury also identifies the seeds of its destruction. Brand purpose will not die because consumers will at some point see through the hypocrisy and realise that brands aren’t as ethical as they claim. (People already think brands are hypocritical and not as ethical as they claim.) Brand purpose will die because it will become an object of ridicule, and because consumers will laugh at it. They’ve already started. Brands will discover that overweening and sanctimonious displays of bandwagon-jumping are toxic, and move on – either to more traditional creativity, or (more likely) to the next fad.

What does that mean for those of us who think that business can and should be a force for good in the world, though? Is the death of brand purpose a positive step, ushering in a world where brands can’t simply pretend to be good? Or does it set back the cause, breeding a generation of consumers who refuse to accept the connection of business and ethics at all?

It’s clear that, if business is to be a force for good, a huge cultural, economic, and legal shift is needed. We have to make it harder to be bad and easier to be good. Neither works without the other.

Making it harder to be bad is simple conceptually and tricky in practice. It requires a robust regulatory regime that penalises business that mistreat employees and the environment, and who foist the cost of their externalities onto society as a whole.

That’s proved hard to bring about in much of the developed world in recent years, ravaged as it has been by right-wing populism, but there are some glimmers of hope. Elizabeth Warren, who contested the Democratic nomination for the 2020 US Presidential election, has campaigned to make the principles of Benefit Corporations mandatory for all businesses with a greater than $1 billion turnover. She won the support of BlackRock’s Larry Fink in the process. BlackRock is the biggest asset manager in the world, and Fink believes that businesses are systemically underrating the risk of climate change in particular. BlackRock is using their enormous influence to shift corporate behaviour in that direction. International efforts to combat climate change seem somewhat back on track, following the wilderness years of Trump, and there are continuing efforts against money laundering and tax evasion.

Gradually, the global financial and regulatory environment is making it harder for companies to harass their employees or commit acts of environmental terrorism. It’s getting harder to be bad. But what about making it easier to be good?

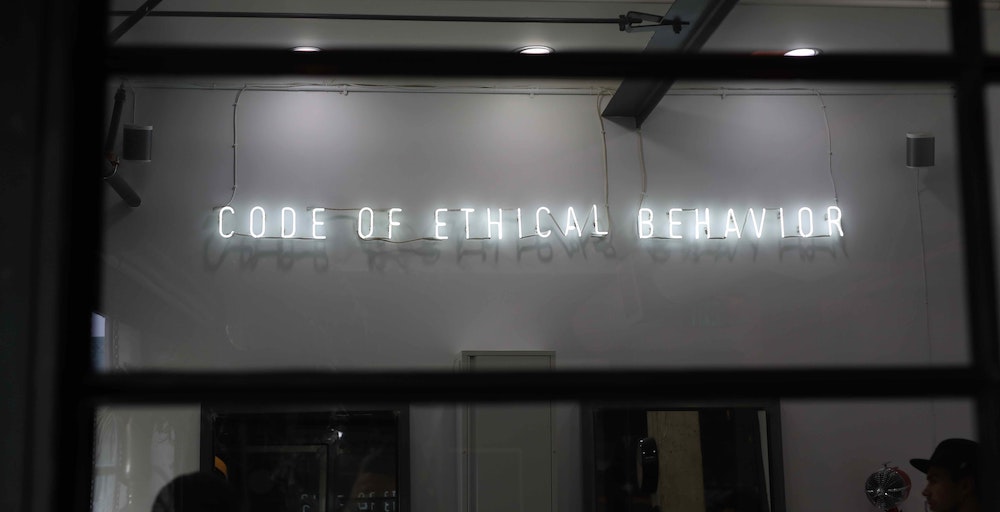

Perhaps the first step is making it easier to understand what a force-for-good business actually looks like, and establishing a consensus on positive cultures and behaviours.

Third parties play a huge part in this. Organisations like B Labs, with their B Corp certification, are lighting the way for aspiring ethical businesses, helping them both to understand what behaviours are good and to find support in their attempts to improve.

But there’s a role for the creative industries in making it easier to be good, too. That doesn’t mean refusing to do a logo for a company unless they’re a B Corp. It doesn’t mean eschewing the profit motive, for us or for our clients. It doesn’t mean suddenly becoming management consultants who can change the fundamental business models of our clients. It means doing the hard yards, the things that are within our wheelhouse.

The first step involves getting our own house in order. The creative industries have shocking issues with gender equality in senior roles, a culture of sexual harassment, low socioeconomic diversity, and racism. In a month when advertising Twitter has been ablaze with stories of sexual harassment, sparked by Zoe Scaman’s hard-hitting Mad Men. Furious Women article, it’s clear that there’s much work to be done. Ethical business starts at home, and starts with the grass roots.

Once that work is done, a more representative creative world might look outwards once more. That might mean seeking out and working with the next generation of ethical businesses, helping to make them famous on their own terms. It might mean influencing our current clients to behave differently in more substantial ways than the content of advertising campaigns. It might mean working with third parties to raise the profile of business as a force for good. Whatever it is, I think we must do something. If the death of brand purpose means that creatives keep their heads down, fail to ask tough questions, and work with anyone who’ll pay them – if we revert as an industry to purely commercial behaviours – then I think we’ll end up somewhere worse than anywhere brand purpose could have taken us.

Add a comment