Commodity AI

Is AI likely to be controlled by a tiny handful of companies, or will it be something accessible to the many?

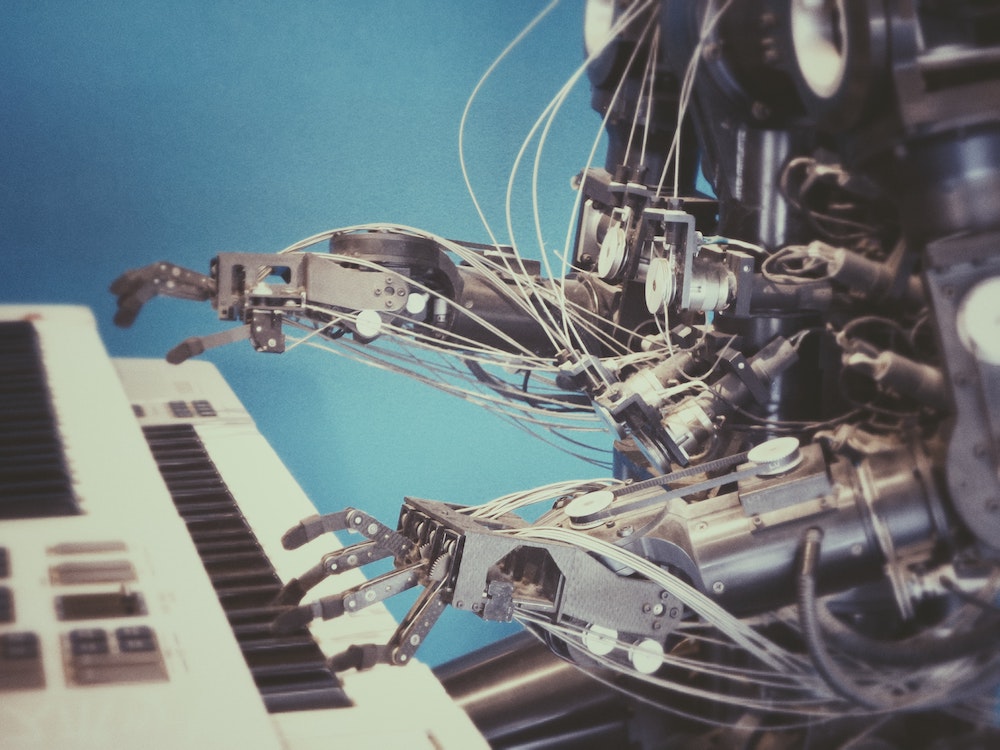

Within the last couple of years, it’s become increasingly clear that useful AI is basically upon us. Not some general-purpose, smarter-than-human intelligence that would take over the world, but AI models that nevertheless can do useful work and make things easier, augmenting work that is still fundamentally directed by humans.

What hasn’t been clear, though, is exactly how the market for AI would shake out. Would we end up with AI controlled by a tiny number of companies who would rule the world? Or would AI be somewhat more democratised, accessible to the many rather than the few?

The three factors that mattered were:

- How much computing resource would be needed in order to train useful models?

- How much expertise and knowledge would be needed to design and fine-tune them?

- How much would having high-quality, proprietary data be an advantage, compared to data that was available to anyone?

The potential outcomes for AI, then, were likely to be one of two scenarios.

The first scenario was that successful and useful AI models would require enormous quantities of computing power, cutting-edge technical know-how, and access to proprietary data that was expensive and time-consuming to collect. In this scenario, AI would be something controlled by a handful of companies. That would likely mean Google and Facebook and a perhaps a few others – the companies that had access to the greatest computing power, developer resource, and proprietary data.

The second scenario was that AI models would have a much lower barrier to creation, requiring resources that were accessible to a far greater number of people and organisations, and usefully trainable on freely accessible data (like that found by crawling the public internet). In this scenario, it’s likely that AI would become something much more recentralised, not owned by any single company, like many past technologies. It might be like the idea of an SQL database, something that’s provided by many different competing providers and that many different businesses make direct use of.

What’s become clear in the last couple of months is that we’re headed to the second scenario. The release of Stable Diffusion and Midjourney have demonstrated that, on all three counts. The amount of compute power to generate the models costs in the region of the single digit millions of dollars – expensive, but well within the reach of countless businesses and even, in Stable Diffusion’s case, wealthy individuals. The technical knowledge necessary is in the public domain; the ML community has shown itself to be remarkably open, and knowledge is shared freely, much more akin to then open publishing of academia than the walled-up trade secrets of Silicon Valley. And finally, the efficacy that can be achieved by training models on large quantities of “dirty” data, such as that found on the public internet, is more than good enough to achieve remarkable results. It’s not necessary to have access to, say, Google’s level of proprietary data.

So, what does that mean? Well, a number of exciting and disruptive things:

- AI is likely to be everywhere – not the foundation of a small number of platforms, but a feature within lots of applications and websites

- AI is likely to be a commodity – low value and accessible to millions, rather than the preserve of a precious few or the basis of significant competitive advantage

- AI is going to be specialised – honed to the needs of specific industries and sectors

- AI is going to develop faster than we can imagine, with contributions from all over the world

AI’s effect on industry, then, is like to be more like the advent of computerisation and automation than some kind of sinister, dystopian, Skynet-like consolidation of power in a tiny number of companies. It’s going to disrupt everything – but it’s more likely to disrupt individual jobs and roles than whole companies or sectors. Just like we have fewer secretaries, hot metal typesetters, and clerks now that we have widespread word processors, desktop publishing systems and spreadsheets, we’re likely to have fewer illustrators, writers, designers, and animators. These are scary times, but what’s clear from this summer’s developments is that they’re no longer just around the corner. They’re here.

Add a comment